Advertisements

Advertisements

Question

What did the Keepers of the zoo reveal to the narrator’s grandfather?

Solution

The tiger licked his grandfather’s hands. A crowd gathered there. A keeper asked grandfather what he was doing. The grandfather told that he had gifted the tiger to the zoo six months ago. The keeper told the grandfather that he had joined the zoo newly. However, he knew that the tiger was bad-tempered. The grandfather wandered about the zoo. He returned to the cage after a little while. Again he stroked and slapped Timothy to bid him goodbye. Another keeper recognized grandfather. He revealed that the tiger was not his Timothy. His Timothy had died two months ago.

APPEARS IN

RELATED QUESTIONS

Thinking about Language

Here are some sentences from the text. Say which of them tell you, that the author:

(a) was afraid of the snake, (b) was proud of his appearance, (c) had a sense of humour,

(d) was no longer afraid of the snake.

1. I was turned to stone.

2. I was no mere image cut in granite.

3. The arm was beginning to be drained of strength.

4. I tried in my imagination to write in bright letters outside my little heart the words, ‘O

God’.

5. I didn’t tremble. I didn’t cry out.

6. I looked into the mirror and smiled. It was an attractive smile.

7. I was suddenly a man of flesh and blood.

8. I was after all a bachelor, and a doctor too on top of it!

9. The fellow had such a sense of cleanliness…! The rascal could have taken it and used it

after washing it with soap and water.

10. Was it trying to make an important decision about growing a moustache or using eye

shadow and mascara or wearing a vermilion spot on its forehead?

Thinking about Poem

How has the tree grow to its full size? List the words suggestive of its life and activity.

1. In 1953, Hooper was a favoured young man. A big genuine grin civilized his highly competitive nature. Standing six-foot-one, he'd played on the university football team. He was already a hard-charging Zone Sales Manager for a chemical company. Everything was going for him.

2. Then, when he was driving home one autumn twilight, a car sped out in front of him without warning. Hooper was taken to the hospital with a subdural haemorrhage in the motor section of the brain, completely paralysing his left side.

3. One of Chuck's district managers drove Marcy to the hospital. Her husband couldn't talk; he could only breathe and see, and his vision was double. Marcy phoned a neighbour, asking him to put Duke in a kennel.

4. Hooper remained on the critical list for a month. After the fifth week some men from his company came to the hospital and told Hooper to take a year off. They would create a desk job for him at the headquarters.

5. About six weeks after the accident, the hospital put him in a wheelchair. Every day there was someone working his paralysed arm and leg followed by baths, exercise, a wheeled walker. However, Chuck didn't make much headway.

6. In March, they let him out of the hospital. After the excitement of homecoming wore off, Chuck hit a new low. At the hospital there had been other injured people, but now, each morning when Marcy quietly went to work, it was like a gate slamming down. Duke was still in the kennel, and Chuck was alone with his thoughts.

7. Finally, they decided to bring Duke home. Chuck said he wanted to be standing when Duke came in, so they stood him up. Duke's nails were long from four months' confinement, and when he spied Chuck he stood quivering like 5000 volts; then he let out a bellow, spun his long-nailed wheels, and launched himself across three metres of air. He was a 23-kilo missile of joy. He hit Chuck above the belt, causing him to fight to keep his balance.

8. Those who saw it said the dog knew instantly. He never jumped on Chuck again. From that moment, he took up a post beside his master's bed round the clock.

9. But even Duke's presence didn't reach Chuck. The once-iron muscles slacked on the rangy frame. Secretly, Marcy cried as she watched the big man's grin fade away. Severe face lines set in like cement as Chuck stared at the ceiling for hours, then out of the window, then at Duke.

10. When two fellows stare at each other day in, day out, and one can't move and the other can't talk, boredom sets in. Duke finally couldn't take it. From a motionless coil on the floor he'd spring to his feet, quivering with impatience.

11. "Ya-ruff"

12. "Lie down. Duke!"

13. Duke stalked to the bed, poked his pointed nose under Chuck's elbow and lifted. He nudged and needled and snorted.

14. "Go run around the house, Duke."

15. But Duke wouldn't. He'd lie down with a reproachful eye on Hooper. An hour later he would come over to the bed again and yap and poke. He wouldn't leave but just sit there.

16. One evening Chuck's good hand idly hooked the leash onto Duke's collar to hold him still. It was like lighting a fuse: Duke shimmied himself U-shaped in anticipation. Even Hooper can't explain his next move. He asked Marcy to help him to his feet. Duke pranced, Chuck fought for balance. With his good hand, he placed the leash in his left and folded the paralysed fingers over it, holding them there. Then he leaned forward. With Marcy supporting him by the elbow, he

moved his right leg out in front. Straightening his right leg caused the left foot to drag forward, alongside the right. It could be called a step.

17. Duke felt the sudden slack in the leash and pulled it taut. Chuck swayed forward again, broke the fall with his good right leg, then straightened. Thrice he did that, then collapsed into the wheelchair, exhausted.

18. Next day, the big dog started early; he charged around to Hooper's good side, jabbed his nose under the elbow and snapped his head up. The big man's good arm reached for the leash. With Hooper standing, the dog walked to the end of the leash and tugged steadily. Four so-called steps they took that day.

19. Leaning back against the pull, Hooper learned to keep his balance without Marcy at his elbow. Wednesday, he and Duke took five steps; Thursday, six steps; Friday, failure- two steps followed by exhaustion. But in two weeks they reached the front porch.

20. By mid-April neighbours saw a daily struggle in front of Marcy's house. Out on the sidewalk they saw the dog pull his leash taut then stand and wait. The man would drag himself abreast of the dog, then the dog would surge out to the end of the leash and wait again. The pair set daily goals; Monday, the sixth fence post, Tuesday, the seventh fence post, Wednesday ......

21. When Marcy saw what Duke could do for her husband, she told the doctor, who prescribed a course of physiotherapy with weights, pulleys and whirlpool baths and above all walking every day with Duke, on a limited, gradual scale.

22. By now neighbours on their street were watching the pattern of progress. On June 1, news spread that Hooper and Duke had made it to an intersection quite far away.

23. Soon, Duke began campaigning for two trips a day, and they lengthened the targets, one driveway at a time. Duke no longer waited at each step.

24. On January 4, Hooper made his big move. Without Duke, he walked the 200 metres from the clinic to the local branch office of his company. This had been one of the district offices under his jurisdiction as zone manager. The staff was amazed by the visit. But to Gordon Doule, the Manager, Chuck said, "Gordon, this isn't just a visit. Bring me up to date on what's happened, will you - -so I can get to work?" Doule gaped, "It'll just be an hour a day for a while," Hooper continued. "I'll use that empty desk in the warehouse. And I'll need a dictating machine. 16

25. Back in the company's headquarters, Chuck's move presented problems -- tough ones. When a man fights that hard for a comeback, who wants to tell him he can't handle his old job? On the other hand, what can you do with a salesman who can't move around, and can work only an hour a day? They didn't know that Hooper had already set his next objective: March 1, a full day's work.

26. Chuck hit the target, and after March 1, there was no time for the physiotherapy programme; he turned completely to Duke, who pulled him along the street faster and faster, increasing his stability and endurance. Sometimes, walking after dark, Hooper would trip and fall. Duke would stand still as a post while his master struggled to get up. It was as though the dog knew that his job was to get Chuck back on his feet.

27. Thirteen months from the moment he worked full days. Chuck Hooper was promoted to regional manager covering more than four states.

28. Chuck, Marcy and Duke moved house in March 1956. The people in the new suburb where the Hoopers bought a house didn't know the story of Chuck and Duke. All they knew was that their new neighbour walked like a struggling mechanical giant and that he was always pulled by a rampageous dog that acted as if he owned the man.

29. On the evening of October 12, 1957, the Hoopers had guests. Suddenly over the babble of voices, Chuck heard the screech of brakes outside. Instinctively, he looked for Duke.

30. They carried the big dog into the house. Marcy took one look at Duke's breathing, at his brown eyes with the stubbornness gone. "Phone the vet," she said. "Tell him, I'm bringing Duke." Several people jumped to lift the dog. "No, please," she said. And she picked up the big Duke, carried him gently to the car and drove him to the animal hospital.

31. Duke was drugged and he made it until 11o'clock the next morning, but his injuries were too severe.

32. People who knew the distance Chuck and Duke had come together, one fence post at a time, now watched the big man walk alone day after day. They wondered: how long will he keep it up? How far will he go today? Can he do it alone?

33. A few weeks ago, worded as if in special tribute to Duke, an order came through from the chemical company's headquarters: ".......... therefore, to advance our objectives step by step, Charles Hooper is appointed the Assistant National Sales Manager."

About the Author

William D. Ellis was born in Concord, Massachusetts. He began writing at the age of 12, on being urged by an elementary-school teacher who discerned his talent at an early age. Ellis's study of the history of Ohio provided him material that he eventually used as the foundation for a trilogy of novels: Bounty Lands, Jonathan Blair:Bounty Lands Lawyer, and The Brooks Legend. Each of his novels appeared on best-seller lists, and the trilogy itself eventually earned its author a Pulitzer Prize nomination. The most important recurring theme in his works is the triumph of survival.

Now, read the play.

List of Characters.

Julliette - The owner of the villa

Maid - Juliette’s maid

Gaston - A shrewd businessman

Jeanne - His young wife

Mrs Al Smith - A rich American lady

Maid: Won't Madame be sorry?

Juliette: Not at all. Mind you, if someone had bought it on the very day I placed it for sale, then I might have felt sorry because I would have wondered if I hadn't been a fool to sell at all. But the sign has been hanging on the gate for over a month now and I am beginning to be afraid that the day I bought it, was when I was the real fool.

Maid: All the same, Madame, when they brought you the 'For Sale' sign, you wouldn't let them put it up. You waited until it was night. Then you went and hung it yourself, Madame.

Juliette: I know! You see, I thought that as they could not read it in the dark, the house would belong to me for one more night. I was so sure that the next day the entire world would be fighting to purchase it. For the first week, I was annoyed every time I passed that 'Villa for Sale' sign. The neighbours seemed to look at me in such a strange kind of way that I began to think the whole thing was going to be much more of a sell than a sale. That was a month ago and now, I have only one thought, that is to get the wretched place off my hands. I would sacrifice it at any price. One hundred thousand francs if necessary and that's only twice what it cost me. I thought, I would get two hundred thousand but I suppose I must cut my loss. Besides, in the past two weeks, four people almost bought it, so I have begun to feel as though it no longer belongs to me. Oh! I'm fed up with the place, because nobody really wants it! What time did those agency people say the lady would call?

Maid: Between four and five, Madame.

Juliette: Then we must wait for her.

Maid: It was a nice little place for you to spend the weekends, Madame.

Juliette: Yes . . . but times are hard and business is as bad as it can be.

Maid: In that case, Madame, is it a good time to sell?

Juliette: No, perhaps not. But still. . . there are moments in life when it's the right time to buy, but it's never the right time to sell. For fifteen years everybody has had money at the same time and nobody wanted to sell. Now nobody has any money and nobody wants to buy. But still. .. even so ... it would be funny if I couldn't manage to sell a place here, a stone's throw from Joinville, the French Hollywood, when all I'm asking is a paltry hundred thousand!

Maid: That reminds me, there is a favour I want to ask you, Madame.

Juliette: Yes, what is it my girl?

Maid: Will you be kind enough to let me off between nine and noon tomorrow morning?

Juliette: From nine till noon?

Maid: They have asked me to play in a film at the Joinville Studio.

Juliette: You are going to act for the cinema?

Maid: Yes, Madame.

Juliette: What kind of part are you going to play?

Maid: A maid, Madame. They prefer the real article. They say maids are born; maids not made maids. They are giving me a hundred francs a morning for doing it.

Juliette: One hundred francs!

Maid: Yes, Madame. And as you only pay me four hundred a month, I can't very well refuse, can I, Madame?

Juliette: A hundred francs! It's unbelievable!

Maid: Will you permit me, Madame, to tell you something I've suddenly thought of?

Juliette: What?

Maid: They want a cook in the film as well. They asked me if I knew of anybody suitable. You said just now, Madame, that times were hard. ... Would you like me to get you the engagement?

Juliette: What?

Maid: Every little helps, Madame. Especially, Madame, as you have such a funny face.

Juliette: Thank you.

Maid (taking no notice). They might take you on for eight days, Madame. That would mean

eight hundred francs. It's really money for nothing. You would only have to peel

potatoes one minute and make an omlette the next, quite easy. I could show you

how to do it, Madame.

Juliette: But how kind of you. ... Thank God I'm not quite so hard up as that yet!

Maid: Oh, Madame, I hope you are not angry with me ?

Juliette: Not in the least.

Maid: You see, Madame, film acting is rather looked up to round here. Everybody wants to do it. Yesterday the butcher didn't open his shop, he was being shot all the morning. Today, nobody could find the four policemen, they were taking part in Monsieur Milton's fight scene in his new film. Nobody thinks about anything else round here now. You see, they pay so well. The manager is offering a thousand francs for a real beggar who has had nothing to eat for two days. Some people have all the luck! Think it over, Madame.

Juliette: Thanks, I will.

Maid: If you would go and see them with your hair slicked back the way you do when you are dressing, Madame, I am sure they would engage you right away. Because really, Madame, you look too comical!

Juliette: Thank you! (The bell rings.) I am going upstairs for a moment. If that is the lady, tell

her I will not be long. It won't do to give her the impression that I am waiting for her.

Maid: Very good, Madame. (Exit JULIETTE, as she runs off to open the front door.) Oh, if I could become a Greta Garbo! Why can't I? Oh! (Voices heard off, a second later, the MAID returns showing in GASTON and JEANNE.)

Maid: If you will be kind enough to sit down, I will tell Madame you are here.

Jeanne: Thank you.

(Exit MAID)

Gaston: And they call that a garden! Why, it's a yard with a patch of grass in the middle!

Jeanne: But the inside of the house seems very nice, Gaston.

Gaston: Twenty-five yards of Cretonne and a dash of paint… you can get that anywhere.

Jeanne: That's not fair. Wait until you've seen the rest of it.

Gaston: Why should I? I don't want to see the kitchen to know that the garden is a myth and that the salon is impossible.

Jeanne: What's the matter with it?

Gaston: Matter? Why, you can't even call it a salon.

Jeanne: Perhaps there is another.

Gaston: Never mind the other. I'm talking about this one.

Jeanne: We could do something very original with it.

Gaston: Yes, make it an annex to the garden.

Jeanne: No, but a kind of study.

Gaston: A study? Good Lord! You're not thinking of going in for studying are you?

Jeanne: Don't be silly! You know perfectly well what a modern study is. Gaston: No, I don't.

Jeanne: Well . .. er.. . it's a place where . .. where one gathers . ..

Gaston: Where one gathers what?

Jeanne: Don't be aggravating, please! If you don't want the house, tell me so at once and we'll say no more about it.

Gaston: I told you before we crossed the road that I didn't want it. As soon as you see a sign 'Villa for Sale', you have to go inside and be shown over it.

Jeanne: But we are buying a villa, aren't we?

Gaston: We are not!

Jeanne: What do you mean, 'We are not'? Then we're not looking for a villa?

Gaston: Certainly not. It's just an idea you've had stuck in your head for the past month.

Jeanne: But we've talked about nothing else....

Gaston: You mean, you've talked about nothing else. I've never talked about it. You see, you've talked about it so much, that you thought that we are talking. . .. You haven't even noticed that I've never joined in the conversation. If you say that you are looking for a villa, then that's different!

Jeanne: Well... at any rate . . . whether I'm looking for it or we're looking for it, the one thingthat matters anyway is that I'm looking for it for us!

Gaston: It's not for us . . . it's for your parents. You are simply trying to make me buy a villa so that you can put your father and your mother in it. You see, I know you. If you got what you want, do you realize what would happen? We would spend the month of August in the villa, but your parents would take possession of it every year from the beginning of April until the end of September. What's more, they would bring the whole tribe of your sister's children with them. No! I am very fond of your family, but not quite so fond as that.

Jeanne: Then why have you been looking over villas for the past week?

Gaston: I have not been looking over them, you have, and it bores me.

Jeanne: Well...

Gaston: Well what?

Jeanne: Then stop being bored and buy one. That will finish it. We won't talk about it any

more.

Gaston: Exactly!

Jeanne: As far as that goes, what of it? Suppose I do want to buy a villa for papa and mamma? What of it?

Gaston: My darling. I quite admit that you want to buy a villa for your father and mother. But

please admit on your side that I don't want to pay for it.

Jeanne: There's my dowry.

Gaston: Your dowry! My poor child, we have spent that long ago.

Jeanne: But since then you have made a fortune.

Gaston: Quite so. I have, but you haven't. Anyway, there's no use discussing it. I will not buy a villa and that ends it.

Jeanne: Then it wasn't worth while coming in.

Gaston: That's exactly what I told you at the door.

Jeanne: In that case, let's go.

Gaston: By all means.

Jeanne: What on earth will the lady think of us.

Gaston: I have never cared much about anybody's opinion. Come along. (He takes his hat and goes towards the door. At this moment JULIETTE enters.)

Juliette: Good afternoon, Madame... Monsieur....

Jeanne: How do you do, Madame?

Gaston: Good day.

Juliette: Won't you sit down? (All three of them sit.) Is your first impression a good one?

Jeanne: Excellent.

Juliette: I am not in the least surprised. It is the most delightful little place. Its appearance is modest, but it has a charm of its own. I can tell by just looking at you that it would suit you admirably, as you suit it, if you will permit me to say so. Coming from me, it may surprise you to hear that you already appear to be at home. The choice of a frame is not so easy when you have such a delightful pastel to place in it. (She naturally indicates JEANNE who is flattered.) The house possesses a great many advantages. Electricity, gas, water, telephone, and drainage. The bathroom is beautifully fitted and the roof was entirely repaired last year.

Jeanne: Oh, that is very important, isn't it, darling?

Gaston: For whom?

Juliette: The garden is not very large . . . it's not long and it's not wide, but…

Gaston: But my word, it is high!

Juliette: That's not exactly what I meant. Your husband is very witty, Madame. As I was saying, the garden is not very large, but you see, it is surrounded by other gardens. . . .

Gaston: On the principle of people who like children and haven't any, can always go and live near a school.

Jeanne: Please don't joke, Gaston. What this lady says is perfectly right. Will you tell me, Madame, what price you are asking for the villa?

Juliette: Well, you see, I must admit, quite frankly, that I don't want to sell it any more.

Gaston : (rising) Then there's nothing further to be said about it.

Juliette: Please, I...

Jeanne: Let Madame finish, my dear.

Juliette: Thank you. I was going to say that for exceptional people like you, I don't mind giving it up. One arranges a house in accordance with one's own tastes - if you understand what I mean - to suit oneself, as it were - so one would not like to think that ordinary people had come to live in it. But to you, I can see with perfect assurance, I agree. Yes, I will sell it to you.

Jeanne: It's extremely kind of you.

Gaston: Extremely. Yes ... but ...er… what's the price, Madame?

Juliette: You will never believe it...

Gaston: I believe in God and so you see ...

Juliette: Entirely furnished with all the fixtures, just as it is, with the exception of that one

little picture signed by Carot. I don't know if you have ever heard of that painter,

have you ?

Gaston: No, never.

Juliette: Neither have I. But I like the colour and I want to keep it, if you don't mind. For the villa itself, just as it stands, two hundred and fifty thousand francs. I repeat, that I would much rather dispose of it at less than its value to people like yourselves, than to give it up, even for more money, to someone whom I didn't like. The price must seem...

Gaston: Decidedly excessive....

Juliette: Oh, no!

Gaston: Oh, yes, Madame.

Juliette: Well, really, I must say I'm.. Quite so, life is full of surprises, isn't it?

Juliette: You think it dear at two hundred and fifty thousand? Very well, I can't be fairer than this, Make me an offer.

Gaston: If I did, it would be much less than that.

Juliette: Make it anyway.

Gaston: It's very awkward ... I... Jeanne. Name some figures, darling .., just to please me.

Gaston: Well I hardly know ... sixty thousand....

Jeanne: Oh!

Juliette: Oh!

Gaston: What do you mean by 'Oh!'? It isn't worth more than that to me.

Juliette: I give you my word of honour, Monsieur, I cannot let it go for less than two hundred thousand.

Gaston: You have perfect right to do as you please, Madame.

Juliette: I tell you what I will do. I will be philanthropic and let you have it for two hundred thousand.

Gaston: And I will be equally good-natured and let you keep it for the same price.

Juliette: In that case, there is nothing more to be said, Monsieur.

Gaston: Good day, Madame.

Jeanne: One minute, darling. Before you definitely decide, I would love you to go over the upper floor with me.

Juliette: I will show it to you with the greatest pleasure. This way, Madame. This way, Monsieur. . .

Gaston: No, thank you . . . really... I have made up my mind and I'm not very fond of

climbing stairs.

Juliette: Just as you wish, Monsieur. (To JEANNE.) Shall I lead the way?

Jeanne: If you please, Madame.

(Exit JULIETTE)

Jeanne (to her husband): You're not over-polite, are you?

Gaston: Oh, my darling! For Heaven's sake, stop worrying me about this shanty. Go and

examine the bathroom and come back quickly.

(Exit JEANNE following JULIETTE)

Gaston (to himself): Two hundred thousand for a few yards of land . . . She must be thinking I'm crazy. . . . (The door bell rings and, a moment later, the MAID re-enters showing in Mrs Al Smith)

Maid: If Madame would be kind enough to come in. Mrs Al Smith: See here, now I tell you I'm in a hurry. How much do they want for this house?

Maid: I don't know anything about it, Madame. Mrs Al Smith: To start off with, why isn't the price marked on the signboard? You French people have a cute way of doing business! You go and tell your boss that if he doesn't come right away, I'm going. I haven't any time to waste. Any hold up makes me sick when I want something. (MAID goes out.) Oh, you're the husband, I suppose. Good afternoon. Do you speak American?

Gaston: Sure . . . You betcha. Mrs Al Smith: That goes by me. How much for this house?

Gaston: How much?... Well... Won't you sit down? Mrs Al Smith: I do things standing up.

Gaston: Oh! Do you? Mrs Al Smith: Yes! Where's your wife?

Gaston: My wife? Oh, she's upstairs. Mrs Al Smith: Well, she can stay there. Unless you have to consult her before you make a sale?

Gaston: Me? Not on your life! Mrs Al Smith: You are an exception. Frenchmen usually have to consult about ten people before they get a move on. Listen! Do you or don't you want to sell

this house?

Gaston: I? ... Oh, I'd love to! Mrs Al Smith: Then what about it? I haven't more than five minutes to spare.

Gaston: Sit down for three of them anyway. To begin with, this villa was built by my

grandfather...

Mrs Al Smith: I don't care a darn about your grandfather!

Gaston: Neither do I. ... But I must tell you that... er...

Mrs Al Smith: Listen, just tell me the price.

Gaston: Let me explain that... Mrs Al Smith: No!

Gaston: We have electricity, gas, telephone...

Mrs Al Smith: I don't care! What's the price?

Gaston: But you must go over the house...

Mrs Al Smith: No!... I want to knock it down and build a bungalow here.

Gaston: Oh, I see!

Mrs Al Smith: Yep! It's the land I want. I have to be near Paramount where I'm going to shoot some films.

Gaston: Oh!

Mrs Al Smith: Yep. You see I'm a big star.

Gaston: Not really?

Mrs Al Smith: (amiably): Yes! How do you do? Well now, how much?

Gaston: Now let's see. ... In that case, entirely furnished, with the exception of that little picture by an unknown artist ... it belonged to my grandfather and I want to keep it. ...

Mrs Al Smith: Say! You do love your grandparents in Europe!

Gaston: We have had them for such a long time!

Mrs Al Smith: You folk are queer. You think about the past all the time. We always think about the future.

Gaston: Everybody thinks about what he's got.

Mrs Al Smith: What a pity you don't try and copy us more.

Gaston: Copies are not always good. We could only imitate you and imitations are no better than parodies. We are so different. Think of it.... Europeans go to America to earn money and Americans come to Europe to spend it.

Mrs Al Smith: Just the same, you ought to learn how to do business

Gaston: We are learning now. We are practising...

Mrs Al Smith: Well then, how much?

Gaston: The house! Let me see. ... I should say three hundred thousand francs. . . . The same for everybody, you know. Even though you are an American, I wouldn't dream of raising the price.

Mrs Al Smith: Treat me the same as anybody. Then you say it is three hundred thousand?

Gaston (to himself): Since you are dear bought - I will love you dear.

Mrs Al Smith: Say you, what do you take me for?

Gaston: Sorry. That's Shakespeare. ... I mean cash. . ,

Mrs Al Smith: Now I get you . . . cash down! Say! You're coming on. (She takes her cheque book from her bag.)

Gaston (fumbling in a drawer): Wait... I never know where they put my pen and ink...

Mrs Al Smith: Let me tell you something, you'd better buy yourself a fountain pen with the money you get for the villa. What date is it today?

Gaston: The twenty- fourth.

Mrs Al Smith: You can fill in your name on the cheque yourself. I live at the Ritz Hotel., Place Vendome. My lawyer is...

Gaston: Who ...?

Mrs Al Smith: Exactly!

Gaston: What?

Mrs Al Smith: My lawyer is Mr. Who, 5, Rue Cambon. He will get in touch

with yours about the rest of the transaction. Good-bye.

Gaston: Good-bye.

Mrs. Al Smith: When are you leaving?

Gaston: Well...er ... I don't quite know . . . whenever you like.

Mrs. Al Smith: Make it tomorrow and my architect can come on Thursday. Good-bye. I'm

delighted.

Gaston: Delighted to hear it, Madame. (She goes and he looks at the cheque.) It's a very good thing in business when everyone is delighted! (At that moment, JEANNE and JULIETTE return)

Gaston: Well?

Jeanne: Well... of course ...it's very charming. ...

Juliette: Of course, as I told you, it's not a large place. I warned you. There are two large bedrooms and one small one.

Gaston: Well now! That's something.

Jeanne : (to her husband). You are quite right, darling. I'm afraid it would not be suitable. Thank you, Madame, we need not keep you any longer.

Juliette: Oh, that's quite alright.

Gaston: Just a moment, just a moment, my dear. You say there are two large bedrooms and a small one....

Juliette: Yes, and two servants' rooms.

Gaston: Oh! There are two servants' rooms in addition, are there?

Juliette: Yes.

Gaston: But that's excellent!

Juliette: Gaston, stop joking!

Gaston: And the bathroom? What's that like?

Juliette: Perfect! There's a bath in it. ...

Gaston: Oh, there's a bath in the bathroom, is there?

Juliette: Of course there is!

Gaston: It's all very important. A bathroom with a bath in it. Bedrooms, two large and one small, two servants' rooms and a garden. It's really possible. While you were upstairs, I have been thinking a lot about your papa and mamma. You see, I am really unselfish, and then the rooms for your sister's children. . . . Also, my dear, I've been thinking . . . and this is serious... about our old age. . . . It's bound to come sooner or later and the natural desire of old age is a quiet country life. . . . (To JULIETTE:) You said two hundred thousand, didn't you?

Jeanne: What on earth are you driving at?

Gaston: Just trying to please you, darling.

Juliette: Yes, two hundred thousand is my lowest. Cash, of course.

Gaston: Well, that's fixed. I won't argue about it. (He takes out his cheque book.)

Juliette: But there are so many things to be discussed before…

Gaston: Not at all. Only one thing. As I am not arguing about the price, as I'm not bargaining with you . . . well, you must be nice to me, you must allow me to keep this little picture which has kept me company while you and my wife went upstairs.

Juliette: It's not a question of value...

Gaston: Certainly not . . . just as a souvenir...

Juliette: Very well, you may keep it.

Gaston: Thank you, Madame. Will you give me a receipt, please? Our lawyers will draw up the details of the sale. Please fill in your name. . . . Let us see, it's the twenty-third, isn't it?

Juliette: No, the twenty-fourth. . . .

Gaston: What does it matter? One day more or less. (She signs the receipt and exchanges it for his cheque.) Splendid!

Juliette: Thank you, Monsieur.

Gaston: Here is my card. Good-bye, Madame. Oh, by the way, you will be kind enough to leave tomorrow morning, won't you.

Juliette: Tomorrow! So soon?

Gaston: Well, say tomorrow evening at the latest.

Juliette: Yes, I can manage that. Good-bye Madame.

Jeanne: Good day, Madame.

Gaston: I'll take my little picture with me, if you don't mind? (He unhooks it.) Just a beautiful souvenir, you know. .

Juliette: Very well. I'll show you the garden, on the way out.

(Exit JULIETTE)

Jeanne: What on earth have you done?

Gaston: I? I made a hundred thousand francs and a Carot!

Jeanne: But how?

Gaston: I'll tell you later.

CURTAIN

About the Author

Sacha Guitry (1885-1957) son of a French actor, was born in St. Petersburg (Later

Leningrad) which accounts for his Russian first name. Given his father's profession,

he became a writer of plays and films. Some of his own experiences with people

engaged in film production may be reflected in Villa for Sale.

Guitry was clever, irrepressible and a constant source of amusement. He claimed that

he staged a 'one-man revolt' against the dismal French theatre of his time. He was

equally successful on screen and stage. Besides being a talented author and actor, he

earned recognition as a highly competent producer and director.

When we write informal letters (to a friend, or to a member of our family) we use this layout.

|

33 Bhagat Singh Road Dear Dad (body of the letter - in paragraphs) Yours affectionately |

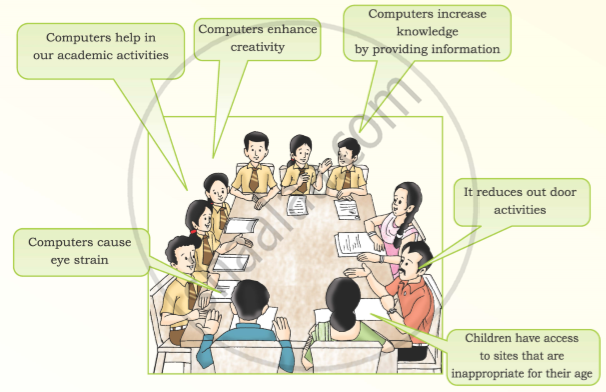

This is a meeting of the school's Parent-Teacher Association. Some student representatives have also been invited to participate to discuss the role that Information Technology I Computers play in the growth and development of children.

Old Kaspar took it from the boy,

Who stood expectant by;

And then the old man shook his head,

And,with a natural sigh,

"Tis some poor fellow's skull," said he,

"Who fell in the great victory.

"I find them in the garden,

For there's many here about;

And often when I go to plough,

The ploughshare turns them out!

For many thousand men,"said he,

"Were slain in that great victory."

Read the lines given above and answer the question that follow.

Why does the poet use a skull?

There was a time when our people covered the land as the waves of a wind-ruffled sea cover its shell-paved floor, but that time long since passed away with the greatness of tribes that are now but a mournful memory. 1 will not dwell on, nor mourn over, our untimely decay, nor reproach my paleface brothers with hastening it, as we too may have been somewhat to blame.

Youth is impulsive. When our young men grow angry at some real or imaginary wrong, and disfigure their faces with black paint, it denotes that their hearts are black, and that they are often cruel and relentless, and our old men and old women are unable to restrain them. Thus it has ever been. Thus it was when the white man began to push our forefathers ever westward. But let us hope that the hostilities between us may never return. We would have everything to lose and nothing to gain. Revenge by young men is considered gain, even at the cost of their own lives, but old men who stay at home in times of war, and mothers who have sons to lose, know better.

Read the extract given below and answer the question that follow.

Why did Seattle wanted to end up the hostilities?

Mr. Oliver, an Anglo-Indian teacher, was returning to his school late one night on the outskirts of the hill station of Shimla. The school was conducted on English public school lines and the boys – most of them from well-to-do Indian families – wore blazers, caps and ties. “Life” magazine, in a feature on India, had once called this school the Eton of the East.

Mr. Oliver had been teaching in this school for several years. He’s no longer there. The Shimla Bazaar, with its cinemas and restaurants, was about two miles from the school; and Mr. Oliver, a bachelor, usually strolled into the town in the evening returning after dark, when he would take short cut through a pine forest.

Read the extract given below and answer the question that follow.

When did Mr Oliver return from the town?

Most terribly cold it was; it snowed, and was nearly quite dark, and evening— the last evening of the year. In this cold and darkness there went along the street a poor little girl, bareheaded, and with naked feet. When she left home she had slippers on, it is true; but what was the good of that? They were very large slippers, which her mother had hitherto worn; so large were they; and the poor little thing lost them as she scuffled away across the street, because of two carriages that rolled by dreadfully fast.

One slipper was nowhere to be found; the other had been laid hold of by an urchin, and off he ran with it; he thought it would do capitally for a cradle when he some day or other should have children himself. So the little maiden walked on with her tiny naked feet, that were quite red and blue from cold. She carried a quantity of matches in an old apron, and she held a bundle of them in her hand. Nobody had bought anything of her the whole livelong day; no one had given her a single farthing. She crept along trembling with cold and hunger—a very picture of sorrow, the poor little thing!

Read the extract given below and answer the question that follow.

Which day of the year was it in the story?

Beside him in the shoals as he lay waiting glimmered a blue gem. It was not a gem, though: it was sand—?worn glass that had been rolling about in the river for a long time. By chance, it was perforated right through—the neck of a bottle perhaps?—a blue bead. In the shrill noisy village above the ford, out of a mud house the same colour as the ground came a little girl, a thin starveling child dressed in an earth—?coloured rag. She had torn the rag in two to make skirt and sari. Sibia was eating the last of her meal, chupatti wrapped round a smear of green chilli and rancid butter; and she divided this also, to make

it seem more, and bit it, showing straight white teeth. With her ebony hair and great eyes, and her skin of oiled brown cream, she was a happy immature child—?woman about twelve years old. Bare foot, of course, and often goosey—?cold on a winter morning, and born to toil. In all her life, she had never owned anything but a rag. She had never owned even one anna—not a pice.

Why does the writer mention the blue bead at the same time that the crocodile is introduced?

Ans. The author mentions the blue bead at the same time that the crocodile is introduced to create suspense and a foreshadowing of the events’to happen.

Read the extract given below and answer the question that follow.

What was Sibia’s life like?

Discuss the following topic in groups.

When a group of bees finds nectar, it informs other bees of it's location, quantity, etc. through dancing. Can you guess what ants communicate to their fellow ants by touching one another’s feelers?

From the first paragraph

(i) pick out two phrases which describe the desert as most people believe it is;

(ii) pick out two phrases which describe the dessert as specialists see it.

Which do you think is an apt description, and why?

Mark the right item.

The greedy couple borrowed the mill and the mortar to make

The king helped the hermit in digging the beds. He even slept on the floor of the hut and lived like a simple man in the hermit’s hut. What lesson we learn from this?

Why the early man was afraid of fire?

Why did Akbar ask Tansen to join his court?

Answer the following question.

Algu found himself in a tight spot. What was his problem?

Read the extract given below and answer the questions that follow:

|

Bassanio: Portia: |

- Who is on trial?

Why is this person on trial? [3] - Explain in your own words Bassanio’s request to portia in the given extract.

What reason does he give for his request? [3] - How does Portia respond to Bassanio's request? What TWO reasons does she give for her response? [3]

- Who does Bassanio refer to as ‘this cruel devil’? What is this person's response to Portia’s words in the given extract? [3]

- How is the ‘cruel devil’ punished at the end of the trial?

How fair, in your opinion, is this punishment? Justify your response. [4]

When Cassius says, ‘My life is run his compass’, he means that ______.