Topics

Physical World and Measurement

Physical World

Units and Measurements

- International System of Units

- Measurement of Length

- Measurement of Mass

- Measurement of Time

- Accuracy, Precision and Least Count of Measuring Instruments

- Errors in Measurements

- Significant Figures

- Dimensions of Physical Quantities

- Dimensional Formulae and Dimensional Equations

- Dimensional Analysis and Its Applications

- Need for Measurement

- Units of Measurement

- Fundamental and Derived Units

- Length, Mass and Time Measurements

- Introduction of Units and Measurements

Motion in a Straight Line

- Position, Path Length and Displacement

- Average Velocity and Average Speed

- Instantaneous Velocity and Speed

- Kinematic Equations for Uniformly Accelerated Motion

- Acceleration (Average and Instantaneous)

- Relative Velocity

- Elementary Concept of Differentiation and Integration for Describing Motion

- Uniform and Non-uniform Motion

- Uniformly Accelerated Motion

- Position-time, Velocity-time and Acceleration-time Graphs

- Position - Time Graph

- Relations for Uniformly Accelerated Motion (Graphical Treatment)

- Introduction of Motion in One Dimension

- Motion in a Straight Line

Kinematics

Motion in a Plane

- Scalars and Vectors

- Multiplication of Vectors by a Real Number or Scalar

- Addition and Subtraction of Vectors - Graphical Method

- Resolution of Vectors

- Vector Addition – Analytical Method

- Motion in a Plane

- Motion in a Plane with Constant Acceleration

- Projectile Motion

- Uniform Circular Motion (UCM)

- General Vectors and Their Notations

- Motion in a Plane - Average Velocity and Instantaneous Velocity

- Rectangular Components

- Scalar (Dot) and Vector (Cross) Product of Vectors

- Relative Velocity in Two Dimensions

- Cases of Uniform Velocity

- Cases of Uniform Acceleration Projectile Motion

- Motion in a Plane - Average Acceleration and Instantaneous Acceleration

- Angular Velocity

- Introduction of Motion in One Dimension

Laws of Motion

Work, Energy and Power

Laws of Motion

- Aristotle’s Fallacy

- The Law of Inertia

- Newton's First Law of Motion

- Newton’s Second Law of Motion

- Newton's Third Law of Motion

- Conservation of Momentum

- Equilibrium of a Particle

- Common Forces in Mechanics

- Circular Motion and Its Characteristics

- Solving Problems in Mechanics

- Static and Kinetic Friction

- Laws of Friction

- Inertia

- Intuitive Concept of Force

- Dynamics of Uniform Circular Motion - Centripetal Force

- Examples of Circular Motion (Vehicle on a Level Circular Road, Vehicle on a Banked Road)

- Lubrication - (Laws of Motion)

- Law of Conservation of Linear Momentum and Its Applications

- Rolling Friction

- Introduction of Motion in One Dimension

Work, Energy and Power

- Introduction of Work, Energy and Power

- Notions of Work and Kinetic Energy: the Work-energy Theorem

- Kinetic Energy (K)

- Work Done by a Constant Force and a Variable Force

- Concept of Work

- Potential Energy (U)

- Conservation of Mechanical Energy

- Potential Energy of a Spring

- Various Forms of Energy : the Law of Conservation of Energy

- Power

- Collisions

- Non - Conservative Forces - Motion in a Vertical Circle

Motion of System of Particles and Rigid Body

System of Particles and Rotational Motion

- Motion - Rigid Body

- Centre of Mass

- Motion of Centre of Mass

- Linear Momentum of a System of Particles

- Vector Product of Two Vectors

- Angular Velocity and Its Relation with Linear Velocity

- Torque and Angular Momentum

- Equilibrium of Rigid Body

- Moment of Inertia

- Theorems of Perpendicular and Parallel Axes

- Kinematics of Rotational Motion About a Fixed Axis

- Dynamics of Rotational Motion About a Fixed Axis

- Angular Momentum in Case of Rotation About a Fixed Axis

- Rolling Motion

- Momentum Conservation and Centre of Mass Motion

- Centre of Mass of a Rigid Body

- Centre of Mass of a Uniform Rod

- Rigid Body Rotation

- Equations of Rotational Motion

- Comparison of Linear and Rotational Motions

- Values of Moments of Inertia for Simple Geometrical Objects (No Derivation)

Gravitation

Gravitation

- Kepler’s Laws

- Newton’s Universal Law of Gravitation

- The Gravitational Constant

- Acceleration Due to Gravity of the Earth

- Acceleration Due to Gravity Below and Above the Earth's Surface

- Acceleration Due to Gravity and Its Variation with Altitude and Depth

- Gravitational Potential Energy

- Escape Speed

- Earth Satellites

- Energy of an Orbiting Satellite

- Geostationary and Polar Satellites

- Weightlessness

- Escape Velocity

- Orbital Velocity of a Satellite

Properties of Bulk Matter

Mechanical Properties of Solids

- Elastic Behaviour of Solid

- Stress and Strain

- Hooke’s Law

- Stress-strain Curve

- Young’s Modulus

- Determination of Young’s Modulus of the Material of a Wire

- Shear Modulus or Modulus of Rigidity

- Bulk Modulus

- Application of Elastic Behaviour of Materials

- Elastic Energy

- Poisson’s Ratio

Thermodynamics

Behaviour of Perfect Gases and Kinetic Theory of Gases

Mechanical Properties of Fluids

- Thrust and Pressure

- Pascal’s Law

- Variation of Pressure with Depth

- Atmospheric Pressure and Gauge Pressure

- Hydraulic Machines

- Streamline and Turbulent Flow

- Applications of Bernoulli’s Equation

- Viscous Force or Viscosity

- Reynold's Number

- Surface Tension

- Effect of Gravity on Fluid Pressure

- Terminal Velocity

- Critical Velocity

- Excess of Pressure Across a Curved Surface

- Introduction of Mechanical Properties of Fluids

- Archimedes' Principle

- Stoke's Law

- Equation of Continuity

- Torricelli's Law

Oscillations and Waves

Thermal Properties of Matter

- Heat and Temperature

- Measurement of Temperature

- Ideal-gas Equation and Absolute Temperature

- Thermal Expansion

- Specific Heat Capacity

- Calorimetry

- Change of State - Latent Heat Capacity

- Conduction

- Convection

- Radiation

- Newton’s Law of Cooling

- Qualitative Ideas of Black Body Radiation

- Wien's Displacement Law

- Stefan's Law

- Anomalous Expansion of Water

- Liquids and Gases

- Thermal Expansion of Solids

- Green House Effect

Thermodynamics

- Thermal Equilibrium

- Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics

- Heat, Internal Energy and Work

- First Law of Thermodynamics

- Specific Heat Capacity

- Thermodynamic State Variables and Equation of State

- Thermodynamic Process

- Heat Engine

- Refrigerators and Heat Pumps

- Second Law of Thermodynamics

- Reversible and Irreversible Processes

- Carnot Engine

Kinetic Theory

- Molecular Nature of Matter

- Gases and Its Characteristics

- Equation of State of a Perfect Gas

- Work Done in Compressing a Gas

- Introduction of Kinetic Theory of an Ideal Gas

- Interpretation of Temperature in Kinetic Theory

- Law of Equipartition of Energy

- Specific Heat Capacities - Gases

- Mean Free Path

- Kinetic Theory of Gases - Concept of Pressure

- Assumptions of Kinetic Theory of Gases

- RMS Speed of Gas Molecules

- Degrees of Freedom

- Avogadro's Number

Oscillations

- Periodic and Oscillatory Motion

- Simple Harmonic Motion (S.H.M.)

- Simple Harmonic Motion and Uniform Circular Motion

- Velocity and Acceleration in Simple Harmonic Motion

- Force Law for Simple Harmonic Motion

- Energy in Simple Harmonic Motion

- Some Systems Executing Simple Harmonic Motion

- Damped Simple Harmonic Motion

- Forced Oscillations and Resonance

- Displacement as a Function of Time

- Periodic Functions

- Oscillations - Frequency

- Simple Pendulum

Waves

- Reflection of Transverse and Longitudinal Waves

- Displacement Relation for a Progressive Wave

- The Speed of a Travelling Wave

- Principle of Superposition of Waves

- Introduction of Reflection of Waves

- Standing Waves and Normal Modes

- Beats

- Doppler Effect

- Wave Motion

- Speed of Wave Motion

- Projectile

- Projectile Motion

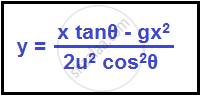

- Equation of path of a projectile

- Oblique projectile

- Time of flight

- Maximum height of a projectile

- Horizontal range

- Horizontal projectile

- Trajectory of horizontal projectiie

- Instantaneous velocity of horizontal projectile

- Direction of instantaneous velocity

- Time of flight

- Horizontal range

Notes

Projectile Motion

What is Projectile?

Projectile is any object thrown into the space upon which the only acting force is the gravity. In other words, the primary force acting on a projectile is gravity. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the other forces do not act on it, just that their effect is minimal compared to gravity. The path followed by a projectile is known as trajectory. A baseball batted or thrown and the instant the bullet exits the barrel of a gun are all examples of projectile.

What is Projectile Motion?

When a particle is thrown obliquely near the earth’s surface, it moves along a curved path under constant acceleration that is directed towards the centre of the earth (we assume that the particle remains close to the surface of the earth). The path of such a particle is called a projectile and the motion is called projectile motion. Air resistance to the motion of the body is to be assumed absent in projectile motion.

In a Projectile Motion, there are two simultaneous independent rectilinear motions:

1. Along x-axis: uniform velocity, responsible for the horizontal (forward) motion of the particle.

2. Along y-axis: uniform acceleration, responsible for the vertical (downwards) motion of the particle.

Accelerations in the horizontal projectile motion and vertical projectile motion of a particle:

When a particle is projected in the air with some speed, the only force acting on it during its time in the air is the acceleration due to gravity (g). This acceleration acts vertically downward. There is no acceleration in the horizontal direction which means that the velocity of the particle in the horizontal direction remains constant.

Parabolic Motion of Projectiles:

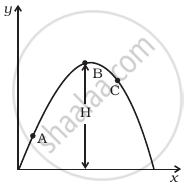

Let us consider a ball projected at an angle θ with respect to horizontal x-axis with the initial velocity u as shown below:

If any object is thrown with the velocity u, making an angle Θ from horizontal, then the horizontal component of initial velocity = u cos Θ and the vertical component of initial velocity = u sin Θ. The horizontal component of velocity (u cos Θ) remains the same during the whole journey as herein, no acceleration is acting horizontally.

The vertical component of velocity (u sin Θ) gradually decrease and at the highest point of the path becomes 0. The velocity of the body at the highest point is u cos Θ in the horizontal direction. However, the angle between the velocity and acceleration is 90 degree. The point O is called the point of projection; θ is the angle of projection and OB = Horizontal Range or Simply Range. The total time taken by the particle from reaching O to B is called the time of flight.

The point O is called the point of projection; θ is the angle of projection and OB = Horizontal Range or Simply Range. The total time taken by the particle from reaching O to B is called the time of flight.

For finding different parameters related to projectile motion, we can make use of different equations of motions:

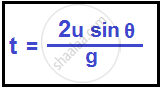

Total Time of Flight:

Resultant displacement (s) = 0 in Vertical direction. Therefore, by using the equation of motions:

gt2 = 2(uyt – sy) [Here, uy = u sin θ and sy = 0]

i.e. gt2 = 2t × u sin θ

Therefore, the total time of flight (t):

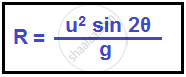

Horizontal Range:

Horizontal Range (OA) = Horizontal component of velocity (ux) × Total Flight Time (t)

R = u cos θ × 2 u sinθ × g

Therefore in a projectile motion the Horizontal Range is given by (R):

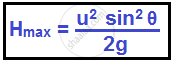

Maximum Height:

It is the highest point of the trajectory (point A). When the ball is at point A, the vertical component of the velocity will be zero. i.e. 0 = (u sin θ)2 – 2g Hmax [s = Hmax, v = 0 and u = u sin θ]

Therefore in a projectile motion the Maximum Height is given by (Hmax):

The equation of Trajectory:

Let, the position of the ball at any instant (t) be M (x, y). Now, from Equations of Motion:

x = t × u cos θ - (1)

y = u sin θ × t –`1/2`×t2g - (2)

On substituting Equation (1) in Equation (2):

This is the Equation of Trajectory in a projectile motion, and it proves that the projectile motion is always parabolic in nature.

A Few Projectile Motion Examples :-

We know that projectile motion is a type of two-dimensional motion or motion in a plane. It is assumed that the only force acting on a projectile (the object experiencing projectile motion) is the force due to gravity. But how can we define projectile motion in the real world? How are the concepts of projectile motion applicable to daily life? Let us see some real-life examples of projectile motion in two dimensions.

All of us know about basketball. To score a basket, the player jumps a little and throws the ball in the basket. The motion of the ball is in the form of a projectile. Hence it is referred to as projectile motion. What advantage does jumping give to their chances of scoring a basket? Now apart from basketballs, if we throw a cricket ball, a stone in a river, a javelin throw, an angry bird, a football or a bullet, all these motions have one thing in common. They all show a projectile motion. And that is, the moment they are released, there is only one force acting on them- the gravity. It pulls them downwards, thus giving all of them an equal impartial acceleration of.

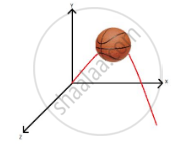

It implies that if something is being thrown in the air, it can easily be predicted how long the projectile will be in the air and at what distance from the initial point it will hit the ground. If the air resistance is neglected, there would be no acceleration in the horizontal direction. This implies that as long as a body is thrown near the surface, the motion of the body can be considered as a two-dimensional motion, with acceleration only in one direction. But how can it be concluded that a body thrown in air follows a two-dimensional path? To understand this, let us assume a ball that is rolling as shown below:

Now, if the ball is rolled along the path shown, what can we say about the dimension of motion? The most common answer would be that it has an x-component and a y-component, it is moving on a plane, so it must be an example of motion in two dimensions. But it is not correct, as it can be noticed that there exists a line which can completely define the motion of the basketball. Thus, it is an example of motion in one dimension. Therefore, the choice of axis does not alter the nature of the motion itself.|

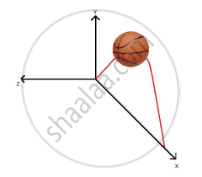

Now, if the ball is thrown at some angle as shown, the velocity of the ball has an x-component and component and also a z-component. So, does it mean that it is a three-dimensional motion? It can be seen here that a line cannot define such a motion, but a plane can. Therefore, for a body thrown at any angle, there exists a plane that entirely contains the motion of that body. Thus, it can be concluded that as long as a body is near the surface of the Earth and the air resistance can be neglected, then irrespective of the angle of projection, it will be a two-dimensional motion, no matter how the axes are chosen. If the axes here are rotated in such a way that, then and can completely define the motion of the ball as shown below:

Thus, it can be concluded that the minimum number of coordinates required to completely define the motion of a body determines the dimension of its motion.

Few Examples of Two – Dimensional Projectiles

-

Throwing a ball or a cannonball

-

The motion of a billiard ball on the billiard table.

-

A motion of a shell fired from a gun.

-

A motion of a boat in a river.

-

The motion of the earth around the sun.